Failure has been all the rage in professional coaching and business circles for nearly a decade (thanks to the book “Fail Fast Fail Often” by Ryan Babineaux and John Krumboltz). The idea is simple: we learn best by making mistakes (or take it from Will Smith). The more the better. From this standpoint, failure is a sign of growth.

Or so the wisdom goes. While most of us want to avoid failing as much as possible, if we’re really trying something hard, something new, something that pushes our boundaries, we’re going to fail. After all, the absence of failure doesn’t equal success – it might just be the absence of trying.

This concept applies doubly to artists. It comes to mind because I promised to let you know what’s on my easel this week, and as it happens, I painted an epic failure today. And, against all odds, I’m happy about it.

After a couple weeks of travels, followed by a couple weeks of intensive business-side activity, I’ve been feeling a strong pull to get back in the studio. I resolved to set up a routine of daily painting come hell or high water. I also schedule my days to make sure the other important things happen, too.

The result has been positive for a few reasons. It feels good to let creativity flow and not worry so much about producing the next masterpiece. If that happens, great. If not, I’ll paint again tomorrow. This may sound a little odd, but I’m truly not even worried about painting something “good.” That’s a fraught word in the art world, I know, but let’s unpack that another day. The point is, I accept what my skills and talents – applied to the best of my ability under today’s circumstances – will bring forth.

I call this a growth phase. My method is simple: follow my interest and curiosity with a loose intensity, and let my intentions guide the work. I try new approaches, play with colors, change up the media, and see what happens. I work quickly and energetically. Mainly because I enjoy it, and also because I feel it imbues the work with life and creates opportunities for happy accidents. I’m tempted to speculate that working quickly also offers a more direct line to the creative subconscious.

Mt. Hood Paradise by Robin Hostick

OIL ON PANEL, 24” x 18”

That said, I feel it’s important to keep a theme in mind to help guide the work. For example, this past week I’ve been painting portraits of mountains. Over the summer I slept under the stars almost 30 nights, most of them in the mountains. Like a squirrel stashing acorns, I gathered enough inspiration to last through the winter.

All wild places are my passion, but mountains hold a special allure. They make me happy; the ineffable, sublime qualities of mountains seem to wash my soul clean. I love the sheer size and power of mountains looming in the background against the delicate beauty of wildflowers and dewdrops. I love the sense of space and freedom. I love the crisp, scented air. And I love the challenge they present – you can’t just buy a ticket to experience a mountain wilderness. It’s earned one step at a time.

In terms of artistic challenge, you could say the same about painting mountains. Although one might think of mountains as a sort of landscape standard, trying to express how I feel about these sublime places and bring forth their essence in daubs of paint offers plenty to think about.

And that’s the point. I aim for a theme that will lead me into new territory. For example, I’ve been enjoying painting rivers all summer (I can’t wait to announce the Wild & Scenic Rivers of Oregon series!). But it’s time to change it up.

Using the method described above, I select inspiration for my subject each day and begin. In this current growth phase, I’m working alla prima, which means I don’t stop until I’m done. I’m also working directly with paint – no sketching or preparation – just going for it. That forces me to make decisions, work with what’s happening, and let the brush flow versus having a clear outcome in mind.

My goal is to find a personal, visual language for expressing these places and how I experience them. I really have no idea how it will turn out, but I can feel something emerging.

Ever struggle with writing a heartfelt card to someone you care about? It’s a little bit like that. Unless you work at Hallmark, the words don’t always come easy. It feels important. You want to get it right. Even if you know generally how you feel, finding the words to express those feelings can take some effort. But when you finally do find the right words, it’s satisfying.

Always one for a wonky phrase, I almost titled this journal entry “Close Sequential Iteration.” But truly, repetition seems to be the key to familiarity. In this case, training the subconscious to make marks (brush strokes) that feel right. Rather than being paralyzed by the thought of creating an epic mountainscape I can ease into the project by trying out different approaches to see what feels best.

Silver Falling by Robin Hostick

OIL ON PANEL, 24” x 18”

And, back to the concept of failure, it’s OK not to like what happens. I learn from that, too. Even if the marks don’t feel right today, some of them do, and tomorrow could be amazing.

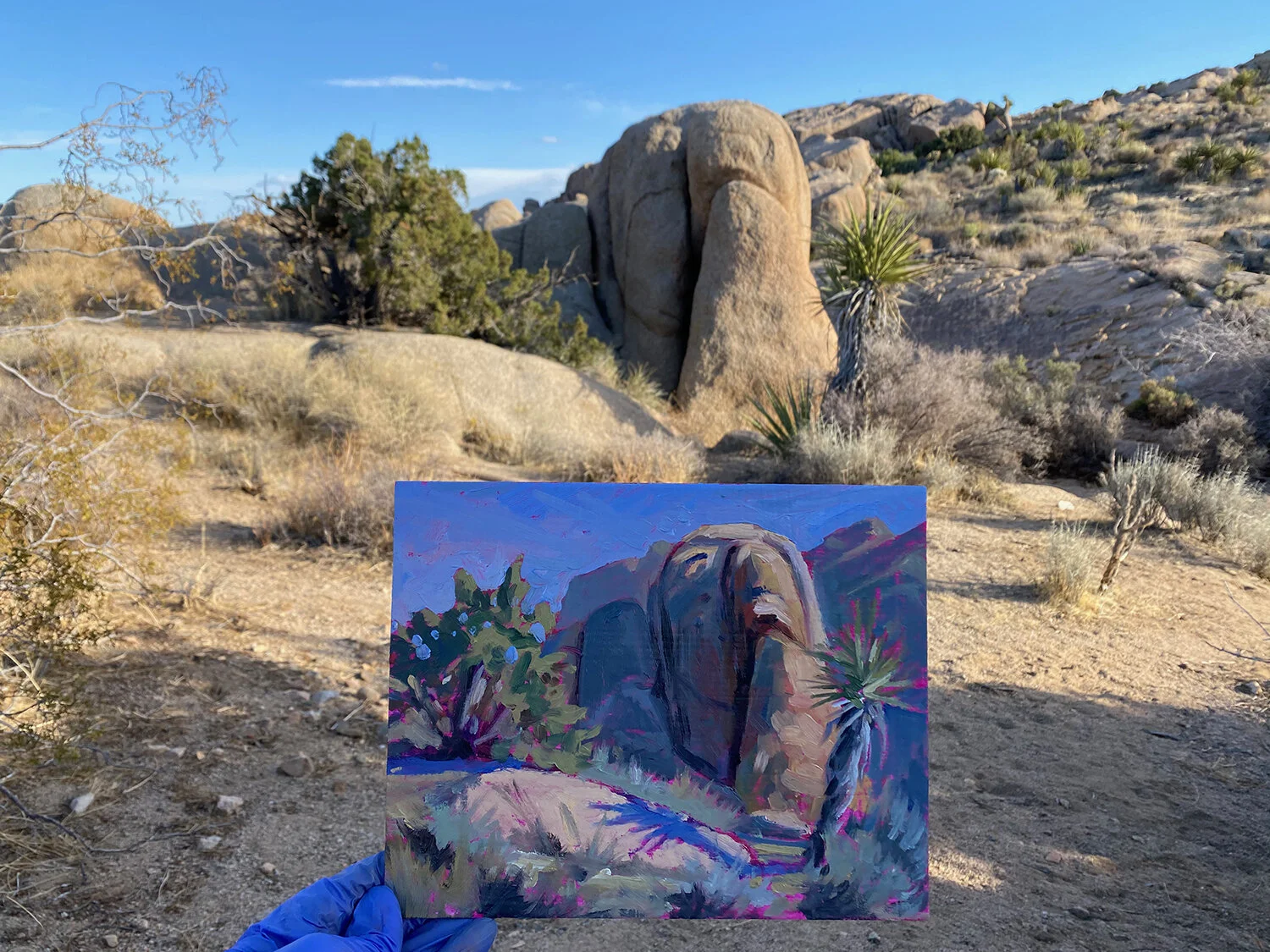

Yes, this is it. The failed painting (see inset). I’m sure this is some sort of artist career blunder, but I can’t tell my readers I’ll share the failures and then not actually do it. “Silver Falling” is an attempted landscape portrait of Oregon’s Silver Falls (South Falls), where I hiked last weekend. Having painted glowing mountains for over a week, painting a dark, wet canyon might have been a shock to my system. After feeling quite certain things weren’t coming together, I attacked the painting with the remains of my palette and was overcome with an urge to let in beams of pink light.

Although this work took a sudden turn from my intentions, it nonetheless express something true about the place, and my relationship with it. There are things I find interesting about it. And it’s different. These are all good reminders to keep intentions loose.

While I subscribe to the “failure is good” idea wholeheartedly, I have a few caveats. First, failure sucks, even if you’ve downed a whole pitcher of Silicon Valley cool aid. Just accept that. And chuckle inwardly. I find that helps. Haha! Oh, well. It’s a kindness to yourself and the product, and opens your mind to possibilities.

Besides, doing something with intention and having unexpected results isn’t necessarily failure. Sometimes just the doing part is a success.

Second, think about why you failed and decide what you’ll do differently next time. Do a little honest sleuthing. Stand back and regard the failure, study it a bit, and ask why? Getting rid of it, never to be seen again, won’t help much. The idea is to learn. Maybe, as in this piece, there are elements you want to keep experimenting with.

Third, try to get all the failing out of the way when the stakes are low. I’m not saying ratchet up the anxiety when the stakes are high. Just the opposite. If you’ve done enough iteration your confidence will match the high stakes efforts.

Plenty of people have expressed skepticism over the “failure” idea, and get a kick out of dueling with semantics. And I have to agree that, while it’s absolutely essential to experiment, iterate, and learn as fast and energetically as you can, my goal as an artist will always be success. We’ll unpack that someday, too.