After six hours of bushwhacking through the steepest, gnarliest forest I’ve ever encountered, we arrived at the bottom of the canyon. Hidden in the shadowy depths of the Devil’s Staircase Wilderness, we’d found the eponymous waterfall at last. Above us, the cool waters of Wasson Creek cascaded down a series of stone ledges, dappled with the waning sunlight, while the silent forest towered above us.

This peaceful moment was eclipsed, however, by one thought: we still had to climb back out – probably in the dark, with no trail to follow. And one of our group members was already near exhaustion.

Back in April, I was thrilled to get an invitation to see Devil’s Staircase, a place I’d heard of as being truly wild and especially difficult to access, if you could find it at all. I’d be joining a group of conservationists, several of whom were experienced off-trail trekkers who had made the journey before.

In the lead-up to the trip, I was duly informed of the risks and strongly encouraged to prepare for a serious outing. I was excited for an adventure. Being an experienced trekker myself, I thought the warnings might have been perhaps a bit exaggerated to make sure everyone took it seriously. Little did I know, they meant every word and then some.

Devil’s Staircase Wilderness, designated in 2019, is one of the newest additions to the National Wilderness Preservation system. It’s part of the Siuslaw National Forest a couple hours’ drive southeast of Eugene. The roads to get there start small and eventually vanish altogether. Two tire tracks through the brush are all that lead to the entry location. Trail rash guaranteed.

The USFS says this about the area: “The Wilderness ... encompasses some of the most remote and rugged terrain on the Siuslaw National Forest, characterized by steep creek drainages, sheer sandstone cliff faces, unstable soils, and dense vegetation. Prior to the Wilderness designation, these steep slopes and unstable soils prevented the area from being logged. These characteristics also make access extremely difficult; there are no established trails within the Wilderness, and navigation is challenging for those who choose to enter.”

This might also be an understatement. So, if you’re reading this and thinking about heading down there for a day trip, you might want to reconsider. Places of equal or greater scenic beauty exist that have at least some kind of trail access. Those are a better bet.

Besides, the real magic of Devi’s Staircase Wilderness is not a spectacular waterfall (it’s nice but the price of admission begs appreciation), or the massive forest (it’s awesome and primal, but the brush will kill you). The real magic is the fact that it’s so remote, so wild, and not really a place for people at all.

I like that about it. In a world where everything is all about people, even the wilderness (if you’ve been out in it lately, you’ll know what I mean), it’s very refreshing to keep a place that’s about being wild. And staying wild.

Not to belabor the point, but in April I had just returned from a long trip in the Southwest during which I’d logged about 200 hiking miles. I was feeling pretty good. Even so, by the time our half of the group climbed out (about 10 hours of bushwhacking), everything hurt. Darkness had set in. During some stretches of the climb out we were literally crawling through the brush on hands and knees.

The other half of the group (who were experienced and well equipped) stayed back to help the member who was having trouble. They made it out safely at about 12:30 am, roughly 14 hours after we started hiking. ‘Nuf said.

But you might ask, what does all this have to do with painting landscapes? An excellent question. Quite a bit, it turns out.

Despite some nagging misgivings about possibly generating interest in this wild place by painting it, I felt a strong compulsion to try. As often happens, however, paint and a two-dimensional canvas seemed to fall short as a medium to convey meaning.

Also typically, my photo references captured only an impression, lacking the scale and immersion one feels when present. Paintings can express considerably more than photographs through the creative process, but even a painting is ultimately an image, bounded and finite.

Ultimately, we must accept that art can’t recreate nature. To try feels silly and hubristic. This wilderness was profoundly humbling and seemed to bring that truth into focus for me. All an artist can hope for is to offer an impression, or perhaps say at least one true thing.

A few weeks ago, I read a great little book recommended to me by an artist I respect. The book is called Hawthorne on Painting. Published originally in 1938, it’s a compilation of notes by Charles W. Hawthorne as he guided his students more than a hundred years ago through the creative process of painting.

Here are a few quotes that caught my attention:

· “Humble yourself before nature, it is too majestic for you to do it justice.” (p.65)

· “It is the artist’s business, the painter’s job to point out to the public the beauties of nature.” (p.54)

· “There isn’t room in your consciousness for more than one sentiment about a thing. Tell that one.” (p.59)

Maybe you need to be a fanatical painter to love these quotes, but I certainly do. Hawthorne’s observations, even a hundred years later, help close the gap for me between expectation and reality. He humanizes the process of painting powerful landscapes

The Devil’s Staircase waterfall, for example, was beautiful, but in a moody, remote sort of way befitting the namesake of such a foreboding place. I had to try painting it, of course. But it needed a dose of romanticism to make it real to me, to say the one true thing.

Digital art is a wonderful medium for experimenting with light and atmosphere. I use an app called Procreate on an Apple iPad Pro. In a short time, I’d created this study.

Devil’s Staircase Waterfall, digital art by Robin Hostick

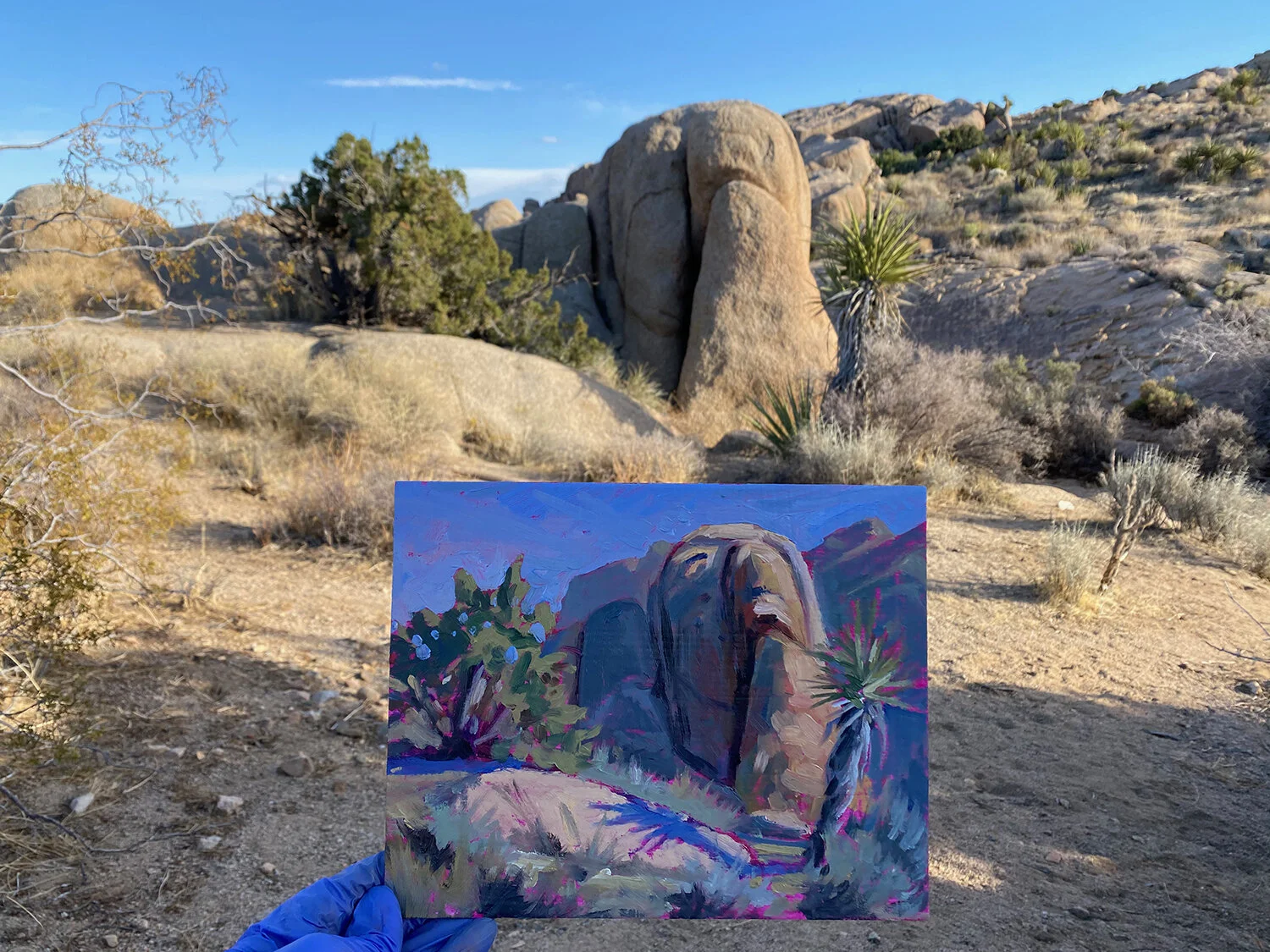

I translated that into a physical painting in acrylic, just to see if and how the atmospheric qualities were transferrable. The result was interesting and quite different stylistically from my other work. It may not be a path I’ll pursue, but experimentation is essential to evolving my process. At least it seemed to say something true about the quality of remoteness and discovery.

The two forest scenes I painted from Devil’s Staircase say something about the way light pours into this precipitously steep, primeval forest on an unseasonably warm, spring evening. There’s much more to say about the scale and presence of being there. But thanks to Hawthorne, I’m content with that for now.

These two paintings will be on display at Studio 7, a rural gallery just west of Eugene, through the end of December. It’s a group show with several other talented, local artists. Stop by and check it out if you get a chance. Check the event listing for details.

On a quick personal note to my subscribers, I’d just like to say thanks for hanging in there this summer. I know my communication has been a bit sparse! It’s been an incredible summer of exploration and growth, and I’m looking forward to sharing a few highlights. We have a lot of catching up to do.

In the meantime, reach out any time if you have questions or observations. I hope you’ve had a wonderful summer, too!