In mid-January, the summit of Mt. Hood is normally frozen solid. That’s a good thing in mountaineering terms because it means loose rocks and ice stay in place and rather than tumble down on your head as you climb.

But as we slogged upward through the deep snow towards the Hog’s Back, the final ridge before the summit pitch, a melon-sized rock hurtled suddenly over the ridge and down the mountain side as though shot from a cannon. We all watched it’s passing, our heads swiveling in unison, and said a few bad words.

We gained the ridge and warily observed the mountain for a while. Occasional ice and rock raced down the face of the mountain, tracing arcs across the cliff-like snow fields. But it seemed to be coming from a particular set of cliffs near the standard route, so we decided to change course.

For about 90 minutes of hard labor, we cut steps with ice axes straight up the frozen snowpack, clinging to the mountain with crampons (boot spikes). At last, we gained the summit ridge to a dizzying landing of hard snow about ten feet square. Although we couldn’t reach the official summit due to the chaos of ice and thousand-foot drop-offs that separated us, this was close enough.

Far below, the rest of the world lay flat as though poured like indigo pancake batter from the mountain’s flanks. Overhead, the winter sky swallowed light in a deep shade of purple-blue. The blackness of space felt close. And while cloud cover spread across the western half of the horizon like a gray duvet, the east glimmered with the dusty beige of the high desert.

The most prominent features in view, however, were the other Cascade summits rising in a great chain, magnificent cones of shining snow stretching north to south.

I’m not much of a mountaineer by any stretch. I just like to be in the mountains any way I can. In the presence of this sublime geography, I forget everything else and find myself in the moment.

In summer, alpine landscapes burst with wildflowers, butterflies, hummingbirds, and babbling brooks. Lungs are filled with the freshest, cleanest air you can find, especially here in the great American West where mountain peaks rise among millions of acres of forest, nature’s great air filter.

Alpine landscapes are tiny, geographic islands of climate, an archipelago of habitat suspended thousands of feet in the air. They’re also tiny islands in time, lasting only a few weeks between the soggy snowmelt of spring and first frost of fall. Autumn brings shocking bolts of color to the aspen and vine maple, blue shadows, and the russet hues of meadows. Spring is a flush of green and the glare of thawing ice.

In winter, mountains preside over a domain of drama and danger. They loom, hidden among the tumult of winter storms until revealed like beacons in a fresh coat of snow. The purity of winter peaks feels distant and unattainable.

Since I was a kid, I’ve had a recurring dream of a beautiful mountain that goes something like this: I find myself at the end of a remote, dirt road. Beyond lies a vast wilderness of canyons and forest. On the other side looms a great, mysterious mountain. I have a compelling urge to go there; somewhere on that mountain something of great interest and meaning awaits. A secret of some kind.

What’s the secret? I’ve spent a lot of time and energy looking for it. And the interesting thing is, I’m never disappointed in what I find.

Maybe, like all dreams, it’s a metaphor. Maybe it’s about facing the unknown. The reward is the journey and the perspective gained from whatever you find along the way.

Or maybe it’s about humility. Mountains remind me that I’m just a tiny human in a huge, timeless universe. Personal illusions simply fall away in the presence of the sublime (but when mountains speak, everybody listens).

Whatever it may be, as a landscape artist I felt it was time to honor the great montane metaphor by painting what I feel.

If you’ve been watching my Instagram or Facebook feeds lately, you’ve probably already seen a lot of mountain paintings. As I foreshadowed in my last journal post, the miniseries is now complete.

I call it “Little Big Mountains,” little paintings of big mountains. I may add a couple more (possibly a future calendar?), but these little gems are now ready for release.

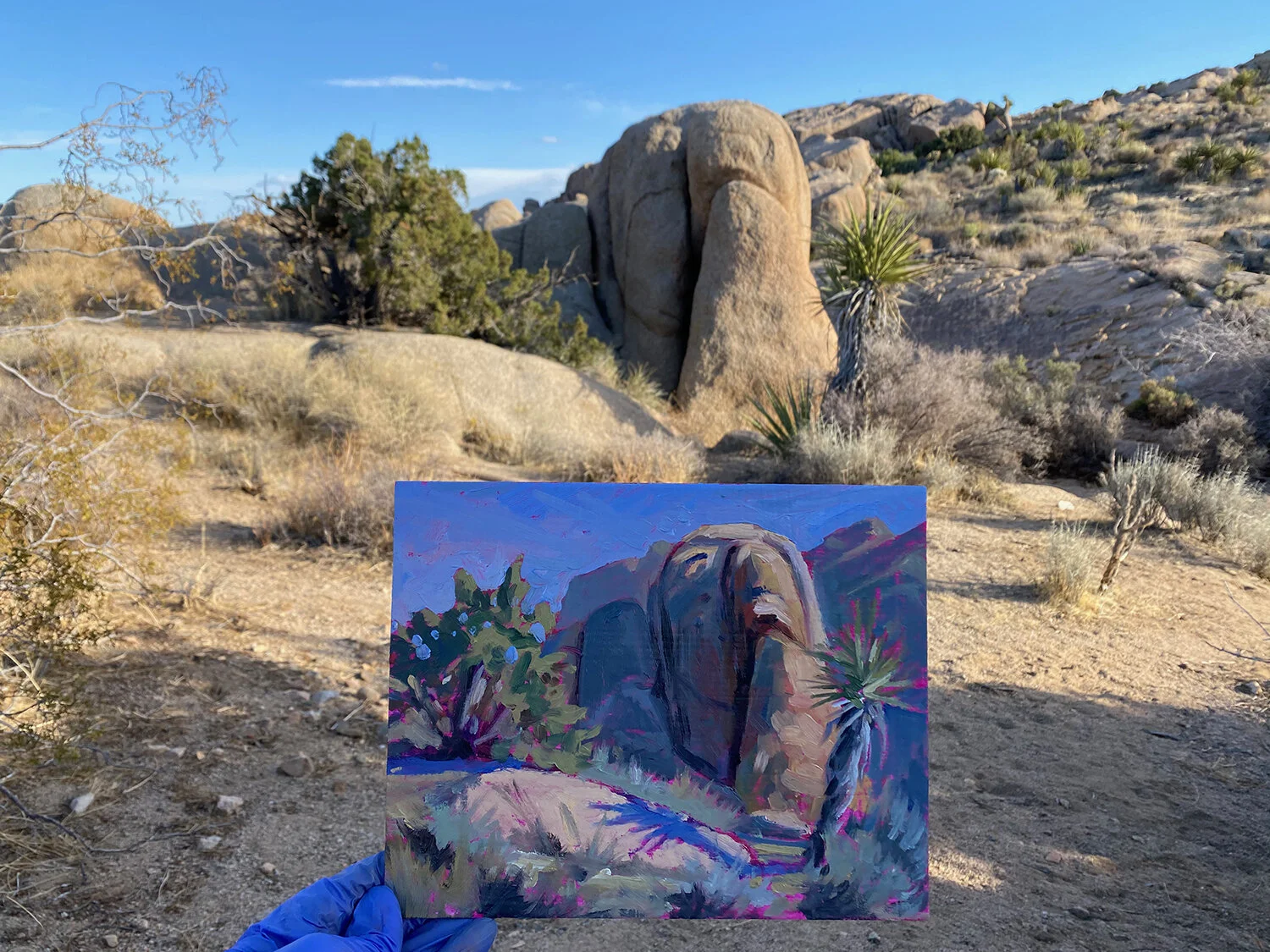

This series is all about getting to know mountains, my distant and aloof muse, in a personal way. I also wanted to develop a technique using acrylic paints and layering of color and tone to emphasize the sense of scale, distance and grandeur. The technique evolved to express the crispness and intense reality of mountain scenes.

Compared to my references, gathered over many years of adventures, these paintings feel like a truer expression of my experience of these wild, beautiful places, which is exactly what I was looking for. By working out the composition beforehand with a sketch, I sought to dial in the essential qualities of the scene and create a balance of light and dark. I set about each successive work with fresh energy and let that show through in the work as much as possible.

Each painting measures 8 x 10 inches, some of the smallest works I’ve created in years. Why? Because the process of iteration is key to growth. And because there are so many beautiful mountains to paint. And because they’re affordable and easy to share with other mountain lovers!

As promised, the “Little Big Mountains” painting series is available exclusively to you, my dear insider list subscribers, starting now through Saturday, February 27th. After that, the paintings will be released to my public web site.

Your special link to the painting series is here: https://www.robinhostickart.com/little-big-mountains.

Thank you for your support and encouragement, and for making it possible to keep creating! It means a lot.