I shimmied along a narrow ledge above a slot canyon somewhere in Anza Borrego State Park. At some point I began to vividly imagine what it might be like to slip and tumble into the narrow void. A trickle of sand and pebbles skittered down from under my feet. Looking back the way I came, I tried to judge the point of diminishing risk/reward. It didn’t look promising, but the alternative was a two-mile detour. Should I go for it?

The problem wasn’t really that we had no choice; just our attachment to the one we’d already made. We’d found our path up the slot canyon blocked by a large stone, impossible to climb. I looked for a way around by scrambling up along the canyon walls.

Fortunately, I remembered my rule of thumb for just these kinds of situations. It goes something like this:

1. Is the goal worthy?

2. Are the consequences of failure low?

3. Is the evident risk of failure easily and reliably surmountable?

The rule is, if the answer is ‘no’ to two or more of these questions, don’t do it. Or, if the answer is ‘yes’ to two or more, go for it!

Slot canyon in Anza Borrego State Park

Back in the slot canyon, all I had to work with was a three-inch-wide, sloped, sand-covered ledge above the canyon. But it looked like others had passed before, and something in my brain’s emotional center said, “If they can do it, so can I!” Ego? Herd mentality?

Fortunately, my rules of risk taking don’t leave room for that kind of thinking. I quickly realized the goal wasn’t worthy, the consequences were pretty bad, and the risk of failure wasn’t nearly as low as it needed to be. So, I happily turned around and took the two-mile detour.

The answer was obvious, of course, which is why good rules of thumb are so helpful. They allow us make decisions less clouded by emotion and impulse.

After thinking about it for a while, I realized these seemingly simple rules of risk taking apply to all kinds of life situations: in the backcountry, at the office, in relationships, or working around the house. I thought I’d share them with you, just in case you ever find yourself asking, “Should I go for it?”

That said, I do find it interesting how reliably outdoor adventure seems to generate life metaphors. One good indicator of an adventure is that it tends to push out other (usually trivial) daily thoughts and concerns, requiring one’s full attention to deal with the more immediate concern of survival. I suppose mental habits are an important part of that process.

Climbing around in the backcountry offers plenty of opportunities to test out this kind of decision making, especially in the American Southwest. Freezing nights, hot days, remote locations, lack of water, exposure, critters, cliffs, canyons, loose rocks, bandits and ghosts all conspire to present a veritable potpourri of risks.

Which is partly why it’s so awesome. That and the stunning beauty, of course.

I spent March and part of April exploring a swath of the Southwest from California to Arizona. My wife joined for the first couple weeks and my daughter for the last couple; in between I explored solo and did some plein air painting.

The purpose of this trip was to gather inspiration for a painting series dedicated to red rock country, a landscape I’ve loved since our family traveled there in my youth (and a few times since then). It’s also a wonderful counterpoint to the Pacific Northwest.

All told, I hiked about 200 miles over all kinds of terrain, usually on trails, but sometimes not. For example, I found myself hiking through slot canyons more often than I expected. Anyone seen the film 127 Hours? Yeah, that was on my mind quite a bit, especially during “solo week.” It might have been that line of thinking that gave rise to my rules of risk taking.

It’s tempting to share a bit of my travel journal with you, but since this is supposed to be an art journal, instead I’ll share something else I learned: painting plein air in the desert is hard.

If you happened to see my Instagram posts (@robinhostickart), you’ll know this already, but it was very cold and very windy on this trip, nearly without exception. We only endured one ice/snowstorm where being outside wasn’t fun at all for about 24 hours, but the rest was at least tolerable as long as you either stayed active or sealed yourself in a sleeping bag. The coldest night was 18 degrees.

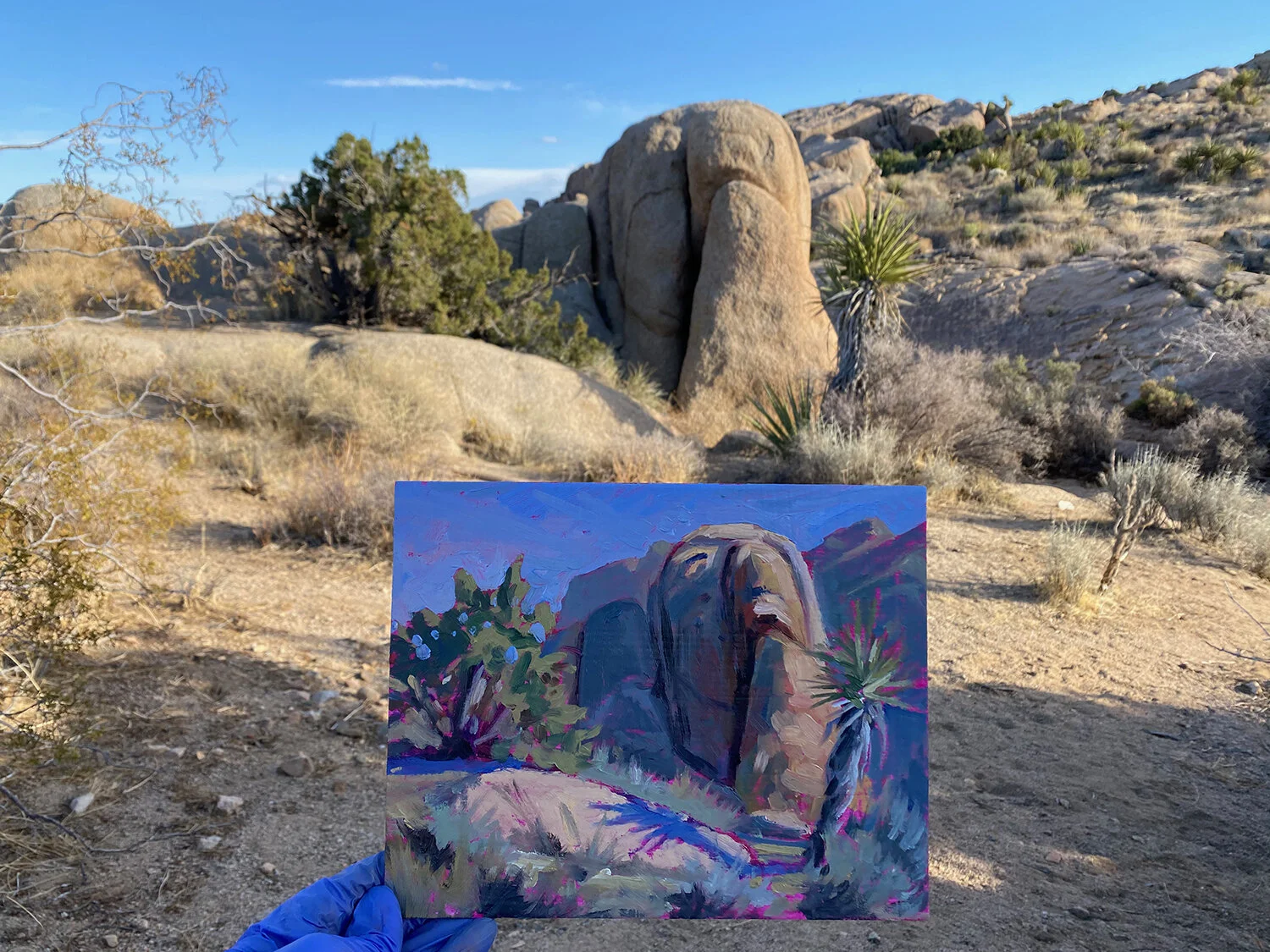

Painting en plein air in Joshua Tree National Park

These conditions aren’t optimal for painting outside. High winds tend to blow things away, tip things over, and fling dust and grit into everything. Finding a place to paint out of the wind is not only difficult but limits your choice of painting subjects.

Cold fingers are also a problem. Painting requires some manual dexterity, and it’s amazing how quickly that can be compromised. Gloves aren’t a great solution, either. Finally, the sun and dry air – welcome as they were – tended to cause my paints to get stiff and skin over.

What to do? First, give the painting a good try. I made a number of sketches and a handful of paintings to get the feel for the place and dial in some colors. Ultimately, however, I decided the best approach was to take as many reference photos as I possibly could and bide my time for a few open weeks in the studio.

The great advantage of this approach is that many amazing, wild, beautiful places are difficult enough to access without trying to lug painting gear. Furthermore, I could cover a lot of terrain and keep moving during times of day when light is the most dramatic and fleeting. My choice of subjects is quite a bit broader and more spectacular than it might be otherwise. Plus, as a nearly lifelong photographer, a fair amount of composition and artistic style is built into the process.

Unfortunately, as much as I’d like to dive in and start painting the series right now, it will have to wait. I’ll be super busy this summer preparing for my first season of Oregon art fairs.

Thus, I plan to start on the red rock series this fall. Besides, it’s also good to give it time to process. I’ll keep you posted.