Our relationships with other people are the single most important driver of our lives and personal happiness. We don’t live in a social vacuum, even in the isolating days of the pandemic. Almost overnight we’ve all learned in such a visceral, personal way how important human contact can be to our wellbeing.

For me, I can’t believe how much I miss being physically close to my friends and family, or being in groups at events, live music, dancing, and parties. I miss that terribly and can’t wait for a return to normal. It’s such a feeling of loss, like my body is still whole but somehow an important part of me has gone missing.

I’ve felt this before. I moved to Germany just after college graduation to live with my soon-to-be fiancé. For a couple of years, I was completely transplanted from my people and my places. I’m not one for homesickness, being an explorer at heart, but I felt a little like I do now, being away from my people. I can talk to them, I know they exist, sometimes I get to see them, but we’re separated by a pandemic ocean.

Thankfully, we returned to Oregon in part because it’s such an amazing place full of natural wonders, which has been a great comfort during the pandemic. Getting out has been our lifestyle for a long time. Now, however, hordes of other people have flocked to the outdoors as well to balance out the stress of the pandemic. As our human relationships have been interrupted, it seems natural that we might start investing in other kinds of relationships.

The idea of having a real relationship with the land is ancient and fundamental to human nature. But the recent turn of events seems to reveal just how out of place that idea has become in our times. I find that interesting. Without the land, of course, there would be no people.

It started me thinking, which is more fundamental to our wellbeing, people or places? On the one hand, we all depend on and ultimately arise from the land. It sustains life with fresh air, water, food and shelter. On the other hand, humans have thrived only because of our social groups, working together to live from the land. We’ve adapted to love, cooperate with, and be close to other people for mutual survival. But just as we don’t exist in a social vacuum, we also don’t exist in a physical vacuum. Relationships between people and places matter.

The answer, of course, is that people and places are both fundamental to our wellbeing. But because of the nature of this crisis, maybe we’ll find ourselves growing closer to the land. That’s certainly been the case for me. The open air is a balm for the pain of separation. I can feel the healing qualities of nature working more directly.

It makes sense. When groups of people feel threatening (COVID dreams, anyone?), the outdoors become inviting. Where cities and closed-in spaces seem risky, the wilds feel free. It’s a strange inversion of instinct. Our ancestors might have felt at risk alone in the wilds and sought the comfort of a family group or village. Today, people are fleeing cities. It may be temporary, but it’s happening.

Always one to seek a silver lining, I’ve made it a point to spend as much quality time as possible with the landscapes I love – both outdoors and in the studio. As it turns out, painting landscapes is a great way to build a relationship.

As with human relationships, it’s also mainly a listening exercise, as social geniuses will tell you. It’s all about spending time with a person, listening, and trying to see someone in the best light. To find out who someone really is, you also need to explore off the beaten track of daily chit chat. Through attention, our fondness grows (notable exceptions notwithstanding). It’s true of many things.

In general, I feel artwork is a gateway to our relationship with the world around us. Sometimes the it’s the subject of a certain artwork that speaks to us. Other times, the style and feeling just strikes a chord that we relate to. Whatever the case, the cornerstone of a relatable artistic expression is the bond between artist and subject.

For example, painting a portrait of a human being is very personal. Sittings can last hours. The artist must observe carefully to capture the essence of a person as they are, at that time, in that context. A skilled portrait artist can express that essence and more, and that expression can endure for hundreds of years.

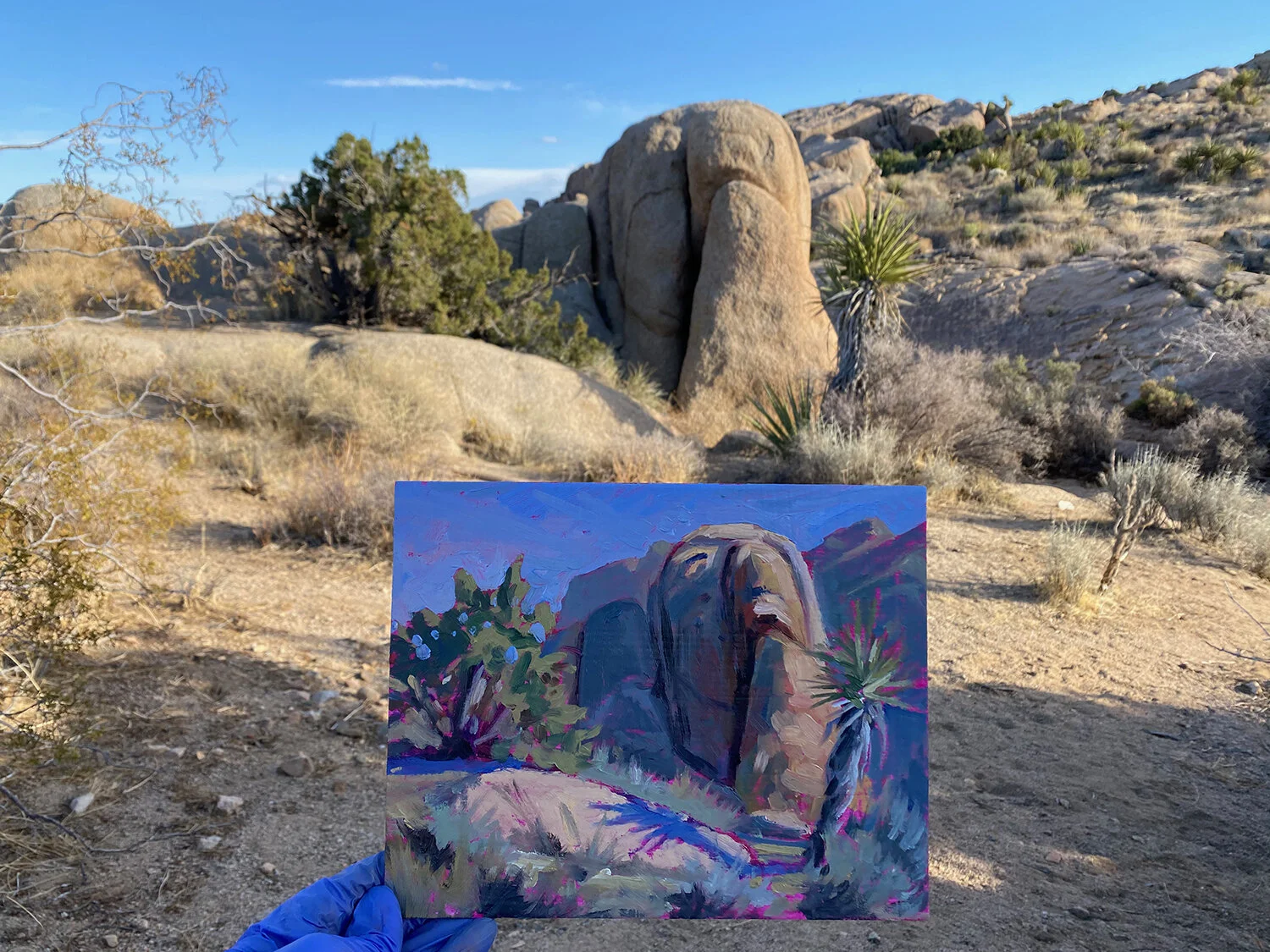

A landscape painting of a real place is similar. In fact, I sometimes describe my work as “portraits of the wild.” Expressing the character and uniqueness, what we love and respond to in the land, is a great challenge.

Like human portraits, landscape portraits also capture something fleeting. Although we tend to think of the land as enduring, the land changes constantly. Naturally, the conditions of light, season and mood are in flux from one moment to the next, but much bigger changes happen, too. During the recent fire season, for example, we saw firsthand that within a few hours or days, places we’ve known our whole lives can be altered forever (the title painting, for example, is of a place that has since burned). Landscape portraits immortalize what we see and feel today.

In the way a crisis can bring people together, I have to wonder if the pandemic and even the fire season might help us bond with places. For me, retreating into the local wonders of Oregon has been personal and revealing. I’m closer to them than I was before, which is saying something.

Maybe because of this - I don’t know - but exploring with the intention to express, honor, and share what I find has begun to take on a kind of responsibility and purpose that I like. Just like caring for my family and friends, it helps give my life meaning. The land is a gift, and it feels good to give something back.