A stretch of mudbanks flanked Deep Creek at the far east end of the Ochoco Mountains. The creek wound in lazy loops across the little valley framed by copper pillars of ponderosa pine. Overhead, nighthawks tumbled in the darkening sky.

I waded along the creek in my sandals, flyrod in hand, casting for trout. On the far side of the mudbank, I could see the concentric ripples of fish rising in a large pool. I thought, oh, what’s a little mud? But after ten steps I was up to my knees and sinking fast.

On most days, fly fishing for trout brings many pleasures. I get to hang out in places I have no other reason to be, standing in a river and only thinking about fishing. There’s the thrill of catching a fish with a tiny fly, the battle to land it, and finally – with any luck – the joy of inspecting the fish up close.

When thinking about the ubiquitous trout, it’s understandable that an ordinary, silvery fish might come to mind. The reality is trout can be stunningly colorful and diverse. And this is especially true of live, wild fish. Many varieties of trout are covered with bright spots, stripes or splashes of red, yellow, orange, olive green, gold, purple and magenta. Some have red fins with white tips, others are steely blue on top and pearly white underneath. Use your imagination, and there’s probably a trout somewhere to match it.

Although fly fishing is a great way to discover trout, there are other ways to get a closer look. From an anger’s perspective, trout might seem pretty skittish about humans flailing around on the riverbank. That may be true, but it turns out trout don’t see humans in the water as much of a threat. It takes a bit of courage, but maybe the best way to have a look at these little beauties is to grab a mask, fins and snorkel and jump in.

Having learned this unusual skill as a kid from my father, I’ve spent many hot summer afternoons with my snorkel gear plumbing the depths of the Santiam, Alsea, Rogue, Applegate, Willamette, Umpqua, Fall Creek, and a handful of other rivers. It’s great fun, and probably the most personal and trout-like way to explore a river.

Eventually I learned to dive to the bottom, grab onto a boulder to hold myself against the current while I observe the fish. From that vantage point, you can see everything, and the fish pretty much ignore you. For as long as you can hold your breath, you get to be part of a different world. It’s like your own personal underwater documentary.

Underwater, the trout aren’t as shy as you’d think – they’re perfectly happy to go about their business snatching flies from the surface. It’s a great way not just to watch the fish’s behavior, but to see their bright colors and markings up close. In my mind’s eye, I can see the summer sunlight playing off the fish right now.

A few months ago, I was exploring the headwaters of the North Fork Crooked River for my partnership with Oregon Wild. I’d heard there was a good population of native redband trout in those waters, so I brought my fly rod (no snorkeling this time, but I won’t rule it out).

I was pleasantly surprised to find that several long stretches of river – on the North Fork and also some tributaries – had undergone some major habitat improvements. The banks had been reshaped, thousands of new plants installed, and tons of logs and woody debris pulled across the stream.

Back to the mudbank story, it would seem all the construction activity had reshaped a lot of deep soil across the valley. The soil had been newly saturated with water when the stream channel was re-directed to find a new course. A perfect recipe for mud. Deep, scary mud.

I tugged at my feet and felt them sink deeper. This is the moment when your fellow adventurer is supposed to throw you a rope, but she was a half mile away. Visions crossed my mind of spending a night stuck in the creek, or worse. Fortunately, at about thigh deep, I hit some rock. With my other foot, I found some slightly more stable ground and after a tense few minutes hauled myself out. After that, I stuck to the gravel banks.

Although the restoration work had been done recently, the habitat already looked great, quicksand notwithstanding. The river channel cast braided loops and pools gathered behind log jams. Fresh willows were popping up. And the fish, though small, were abundant in these areas. I finally caught a couple of the little buggers – the native redbands – and sure enough, they were beautiful. Another living jewel for the memory box.

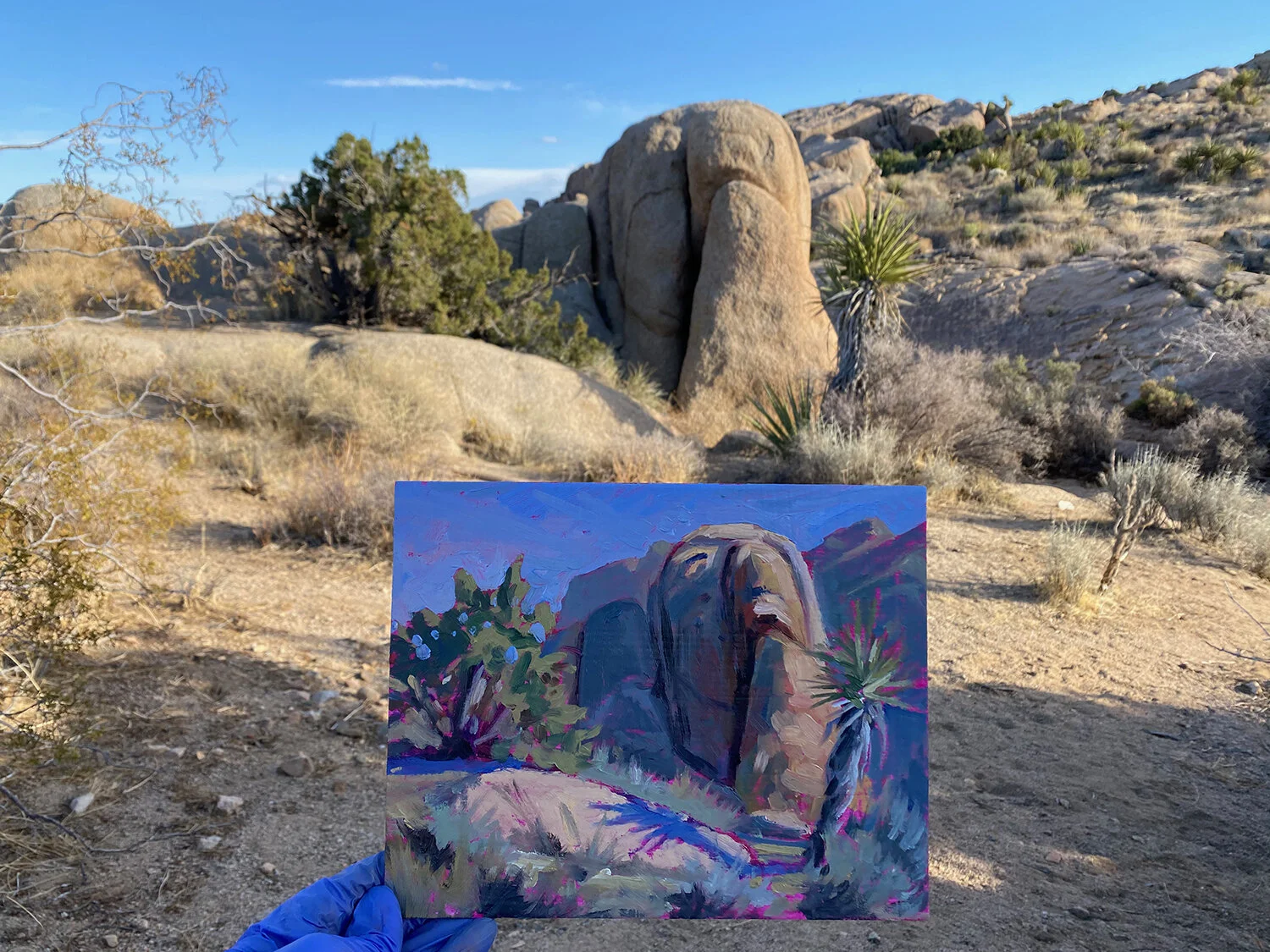

“Native Redband” by Robin Hostick

These redband trout are special in part because they tolerate higher water temperature and lower oxygen levels than other kinds of trout. As our river systems warm up with the predicted hotter, drier summers, that could be an important adaptation. Making sure the redband trout have enough habitat to thrive is wise stewardship.

Will my kids’ kids be able to see these fish in the wild? I certainly hope so. That’s why I’m working to support the National Wild & Scenic designation for the headwaters of the North Fork Crooked River (along with many other wild Oregon rivers). As I mentioned in the videos, the painting of the North Fork Crooked River – just near the junction of many of these special headwater streams – brings to mind these beautiful fish. I can still see them flitting in the pools or darting up from the shadows to snatch a fly.

As of this writing, the original painting and special-edition prints are still available, with 25% going to Oregon Wild to support the Wild & Scenic designation. We’re watching the legislative activity and will keep you updated when the proposal is introduced.